From Pastor Jess:

Rev. Jess Lambert’s Sermon from January 25, 2026

Geography matters. It means something about who you are if you have lived in one place your whole life, and it matters if you, like me, have hopped, skipped and jumped all over the place for most of your life. Geography communicates more than just a location. It’s more than just a dot on the map or the last set of instructions on your GPS. Geography holds memory. It sets in motion the future. One time my mother and I visited the suburb outside Milwaukee where we had lived when I was 3 and 4 years old. Even though I hadn’t been there in over 20 years, there were streets and landmarks that sang to me of familiarity. I was here, by this garden shop. This was the way home. Turn here. This place is part of me somehow.

The geography of Ground Zero carries such heavy weight for so many, whether they were there in 2001 or not. When I lived in Manhattan, whenever I emerged from the subway, I looked for the twin towers to orient myself- which way is west from here? When the towers were gone, the feeling of being lost all the time was ubiquitous. Imagine how hard it must have been to be part of the team which had to imagine a new geography that could inspire a hopeful future, while honoring and keeping sacred the old, the memory of what and who was lost.

Geography matters. It affects us even when we are not aware of it. There are places you cannot get out of your system, no matter how long you’ve been away. And there are places from which you can’t get away soon enough. In our nation right now, we are witnessing the geography of vendettas, cruelty and state sanctioned murder. Portland, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., now Portland and Lewiston, Maine- cities and states with elected leaders who speak out against the lies and the violence and threats coming from the White House, who resist the move towards tyranny. They are targets, and together, they form a map of retribution. Renee Good was killed here. Alex Pretti right here.

A 5-year old child was dragged out of a car and kidnapped over there. Those sites are now memorials, places of worship and protest.

Geography matters.

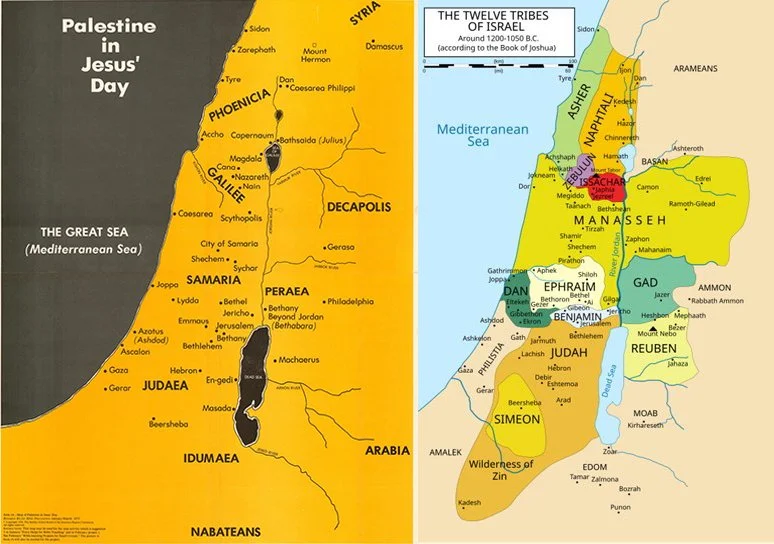

So, when the Gospel writer Matthew tells us that Jesus left Nazareth and made his home in Capernaum by the Sea, in the territory of Zebulun and Naphtali, we should pause, take out the map, and figure out what Matthew means to say by quoting Isaiah and being so specific about these places. There are two maps, one of which is a map of Palestine in Jesus’s time. You can find Capernaum up near the top of the Sea of Galilee.

Do you see the territories of Zebulun and Naphtali there? No, you don’t. They’re not there. Interesting. This map won’t help us. We need a different map to help us, one from about 700 years earlier, when these two tribes of Israel, Zebulun and Naphtali, were conquered by the Assyrians. That’s on the next page. See them there?

In other words, Zebulun and Naphtali have not been part of the daily lives of God’s people for a very, very long time. They were literally wiped off the map 700 years before Jesus decides to go live in Capernaum.

So, why is Matthew even mentioning them? It can hardly be a map mistake. This is not the first, nor the last time Matthew has used geography to make a point and say something important about God. If the art of map making is called cartography, then what Matthew is doing here might be called a cartography of promise, so that what had been spoken through the prophet Isaiah might be fulfilled. 700 years after their obliteration and conquest, 700 years after those tribes of Israel had been dragged away in chains to live in exile, the people in that very same land of Zebulun and Naphtali, will hear once again God’s word of promise!

Jesus is born in Bethlehem, baptized by John in the Jordan, tempted by the devil in the desert, and now begins his public ministry in Galilee, the former territory of Zebulun and Napthtali, and the prophesy of Isaiah 9 is fulfilled! “Land of Zebulun, land of Naphtali, on the road by the sea, across the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles, the people who sat in darkness have seen a great light. And for those who sat in the region and shadow of death, on them light has dawned!”

So Jesus begins his ministry in a place, and for a people, blanketed in darkness- 700 years ago, and still. Wiped off the map, but not out of the heart of God. Erased, perhaps, from the conscious memory of the people,

but not from that silent reservoir of memory which continues to shape them in unknown ways, and never from the memory of God. God is faithful and keeps promises. Unto us a child is born. The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light. Jesus is the light who comes into the darkness and cannot be overcome.

Jesus makes his home in Capernaum, a town occupied by Rome, just as the territories of Zebulun and Naphtali were occupied so many years ago by Assyria. Jesus makes his home in a place sacred to his ancestors but dead, for all intents and purposes, at this point. Jesus goes there to say, “rise from your graves, Zebulun and Naphtali. Rise, and be counted.” He’s come like the strongman in the parables, who crashes into the house at an unknown hour in order to plunder it and take what truly belongs to God. It may look like empire is in control, but you will know the truth, and it will set you free.

The first thing he does in this profoundly important territory is call his first disciples, those who will help him share the news of what God is doing, and we need to understand a few things about their geography as well, these fishermen.

In a book called, Jesus for Farmers and Fishers, the author describes what fishing was like on the Sea of Galilee in the first century. The species the future disciples were likely fishing for was a kind of tilapia that was unique to that body of water. To catch these fish, fishers would find freshwater springs within the salty water and put down their nets there.

Because of the pressure brought to bear by the Roman Empire and its desire to squeeze every last penny from the people of Galilee, that region faced one of the worst farming and fishing crises ever “recorded in the Western world.” The Romans were demanding new taxes, fees, tributes, rents, and tithes.

They employed enforcers throughout the land, meaning that the people, especially peasants, were suffering under new forms of oppression. “Within a span of a single generation, the Galileans had seen nearly two-thirds of their annual catch at sea and their harvest from the land shunted from them in order to support the urban elite and a distant aristocracy,” the author writes.

In this midst of this crisis, in a dead territory, Jesus called his first disciples, and he called them away from the waters. Why did he call fishers first? The primary metaphor for Jesus himself is shepherd, so why weren’t the first disciples shepherds? Jesus was a carpenter, so why not carpenters? Many of Jesus’ parables were about farming, so why were those first called not farmers?

Fishing is an interesting metaphor for the call to follow Jesus. Fishing is nothing if not unpredictable. There are no guarantees, and you are subject to a large number of factors outside your control. At the same time, fishing is a form of constant discernment. Reading the water, assessing temperature and light, noting the food sources that are hatching. Successful fishing isn’t dumb luck. It’s a way of combining careful observation with intuition — with inner knowing.

Fishing also requires patience: there’s a steadiness of focus, a willingness to come up empty, periods of long waiting without fruition. And patience is part of what makes fishing all about surprise. The “big catch” comes when you least expect it, often when you’ve given up hope all together. This willingness to accept the vagaries of human experience and revel in life’s surprises might have been valuable attributes in the uncertain path that Jesus was asking these fishermen to follow.

Fishing involves a fascination with what is below the surface, with where precious things might be hiding, and how we might go about finding them. It involves both familiarity and mystery. We don’t know why he called these people in particular, but in the very next chapter, Jesus will begin to instruct them on who and what he needs them to be in all kinds of situations- in places where they will be persecuted; in the midst of overwhelming power and pressure and the threat of danger; when it would be so easy to give up.

When Jesus calls the fishers from the shore, he calls them from deprivation to abundance, from fear to joy, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. This is the uncharted path they are now asked to walk. Their response to Jesus’s call tells us in yet another way that the reign of God is very near. They drop everything they have ever known, and follow. No matter what blanket of darkness is over us, no matter the cartography that is being drawn around us of fear, death and destruction, we can’t give in or give up. Jesus dwells among us and is infusing all of the dead, dark, forgotten parts of us and our world with light and life. He is enveloping us in a cartography of hope and promise, leading us to locations of resistance, rebirth, and love of neighbor.

We do not have to be afraid. We aren’t lost. We just have to follow. Jesus is the map. Amen.

Rev. Jess Lambert